Our private bespoke tours of Old Quebec are tailored live. Most of the time, the content and itineraries are designed on the spot according to the clients’ pace, interests, etc. Occasionally, some research work is done in advance, as is the case for Robin Boger, who is searching for her ancestors who passed through Québec City & Lévis in 1866.

Tours Accolade was tasked with tracing their journey through Québec City and providing Robin with an understanding of what her ancestors had seen and experienced. This included identifying where their ship had likely docked, and which buildings currently standing had been in existence then. This article aims to present a portion of this research.

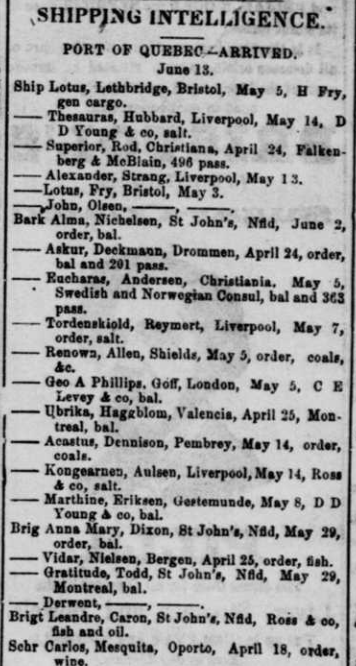

Using what she knew of her family history – that her grandmother, Cristina Birte Solum and her family had left Drammen, Norway on the barque Askur, and sailed to Québec City in 1866 – we were able to find the passenger list for the ship and the date of its arrival. From the ship manifest, we learned that Christina was listed as being 13.75 years old (the fare increased at age 14) and the number, sex and ages of the other passengers on board. We were also able to locate newspapers from the time (in both French and English) that reported on the ship’s arrival, as well other other items of local importance. All of this information served to make the experience much more real for her.

A Journey through Time: Québec City & Lévis in 1866

Coincidentally, 1866 holds significant historical importance for Québec City. It marks the final year of Québec City’s status as the capital of the United Province of Canada before it transitioned to becoming solely a provincial capital. It would later go on to become the national capital, but let’s set politics aside.

In October 1866, the Great Fire of Québec City occurred, devastating a significant portion of St. Roch and wiping out St. Sauveur. Contemporary accounts estimated that around 20,000 people were left homeless before winter. Robin’s ancestors, who arrived in mid-June of the same year, likely left the old capital before this disaster struck.

Only two decades earlier, fires had razed the suburbs of St. Roch, St. Jean, and partially St. Louis. By 1866, these suburbs had already been rebuilt and must have presented an impressive sight.

During that time, less than half of the territory had access to running water, at least for a few hours a day. Citizens could send messages via telegraph, but there were no telephones or electricity. Some streets were illuminated by gaslights, and patrolling officers ensured safety. During the day, pedestrians had to navigate through the bustling streets with over 2,000 horses pulling carriages and carts. The streets were predominantly made of dirt, and whenever sidewalks were present, they consisted of wooden planks. As for snow removal, there was still significant room for improvement.

Commercial activity in the city remained intense, but Québec City was still a garrison town with a defensive system that somewhat restricted traffic. The military authorities had to deal with merchants, and vice versa.

Québec City was no longer just an old city dating back to New France; it was increasingly adorned with modern buildings that reflected the architectural trends of the time. Additionally, a new prison was soon to be constructed. The Lower Town continued to expand, with docks extending further into the river.

The dynamic of the city was clearly initiated: Québec City continued to grow, expand, and modernize. However, the dredging of the river had a significant impact, propelling Montreal’s growth at a faster pace than Québec City. As a result, it was only a matter of time before Montreal took over as the country’s economic center, surpassing Québec City. This shift, to our great pleasure, is actually one of the main reasons behind the preservation of the architectural heritage in the old neighborhoods of city.

As for Lévis, it greatly benefited from the arrival of the train along its shores and continued its rapid growth. It also became fully integrated into Québec City’s defensive system, with three forts under construction, serving as a reminder of the delicate peace between the British Empire and the United States, as the American Civil War came to an end in 1865, while Fenians and Russians represented a threat.

Exploring 1866’s Architectural Landscape

Here, we will present you with a sample of buildings of Québec City in 1866. Some have disappeared over time, while others have survived, either evolving or remaining unchanged. However, you won’t find the Château Frontenac, Price Building, or the Québec National Assembly in this list, as they are all more recent structures.

Preserved Gems: Architectural Treasures of 1866 Still Thriving

Listing all the buildings that existed in 1866 and have survived to this day, with their various significant evolutions, would be an extensive task. Instead, this selection will present buildings of different architectural styles, uses, and periods.

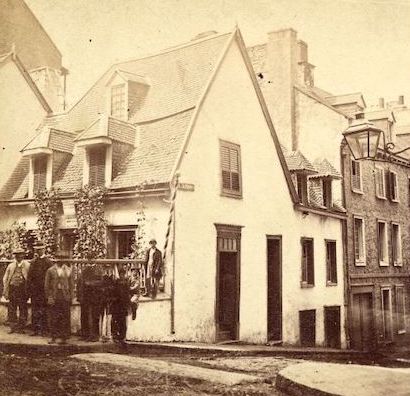

Jacquet House

Built in 1677 on Saint-Louis Street, this building has undergone slight changes over time, such as having a metal roof today. Nonetheless, it remains one of the finest examples of a typical residence in the Upper Town during the second half of the 17th century.

In this image, we see John Williams, the barber, who was located on Saint-Nicolas Street in 1866 and 1867. He later moved to this house.

Today, the building houses the restaurant “Aux Anciens Canadiens” which offers a selection of dishes that may closely resemble the cuisine of that era.

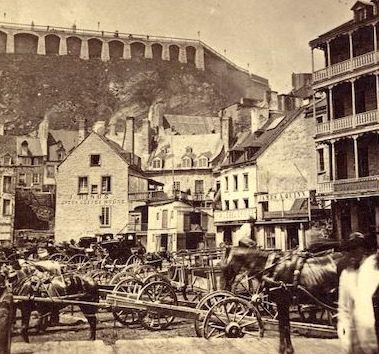

Chevalier House

The Chevalier House is actually a complex comprising three different houses dating back to the late French regime. During the 1860s, it still retained the London Coffee House, which continued to operate for several more decades.

Take note of the presence of numerous carts and horses, as well as the Durham Terrace located above the cliff.

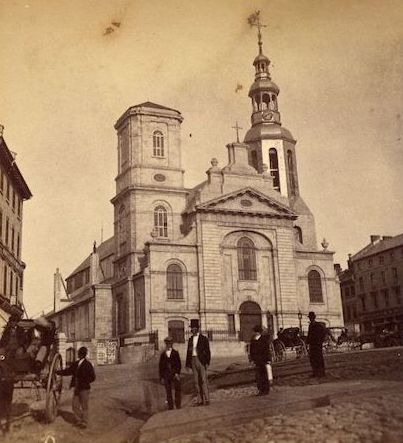

Catholic Cathedral-Basilica Notre-Dame-de-Québec

Located just a few steps from Côte de la Montagne, the site has been home to a church since 1647. Over the years, it has been renovated, embellished, and expanded, but also reconstructed on multiple occasions.

Its current appearance dates back to 1843-44, as it was later reconstructed in the 1920s and 1930s based on the original plans and period photographs, with slight differences.

Anglican Cathedral Holy Trinity

After the Conquest, the Recollet brothers gave way to the Anglicans, who built a cathedral on the site in the early 19th century.

Influenced by the Palladian and neo-classical architectural styles, the cathedral finds its inspiration in London’s St. Martin-in-the-Fields church. The plans are a copy from the London counterpart, the interior nearly replicates it in perfect harmony, while the exterior takes inspiration from the design. Due to the colony’s limitations in budget, materials, and the challenges posed by the local climate, certain modifications were necessary. Notably, in 1818, the roof was altered to a steeper pitch to better withstand the snowfall.

The bells have been ringing from the cathedral since 1830.

Pavillon Camille-Roy

Laval University was founded in 1852 and commissioned Charles Baillargé to construct a new building within the Seminary complex. The construction was completed in 1856.

It retained its flat roof until 1878, making this immense building a valuable clue for dating archival photos. Today, you can still admire the Camille-Roy Pavilion with its magnificent mansard roof, three spires, and the Séminaire’s flag proudly waving atop it.

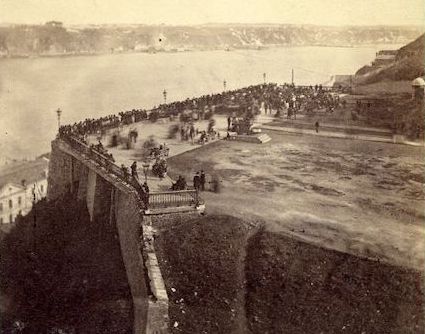

Durham Terrace

In January 1834, the Château Saint-Louis was engulfed in flames and destroyed. The ruins were subsequently covered, and in 1838, an expanded terrace was built, which underwent further enlargement in 1854 and 1879 to become the famous Dufferin Terrace.

Today, you will find the funicular, the statue of Champlain, and most of the time street performers, musicians and singers entertaining the visitors.

Clarendon Hotel

The Clarendon Hotel consists of two buildings: the one on the street corner, dating back to 1858, and the Art Deco-style building on the right, which was constructed in 1927.

The Derbishire & Desbarats printing workshops occupied these premises. However, in 1866, the Clarendon House Hotel opened its doors, making it the oldest hotel still in operation in Quebec City.

General Wolfe’s Corner

It was in the 1780s that a first building was erected at the street corner, featuring a statue of General Wolfe. However, the property seen in the photograph dates back to 1847, but it still displays the statue.

Here’s an amusing anecdote from Jean-Marie Lebel: “In 1838, the statue was removed by sailors who had been celebrating at the Albion Hotel. They brought it aboard the ship L’Inconstant. Onlookers thought they were transporting a drunken companion. The statue was taken to Halifax, Bermuda, and England. It returned a few months later, freshly repainted, and was reinstalled until 1898.”

The empty pedestal is still visible, and to admire the original statue, one simply needs to visit the library at the Morrin Centre.

The Telegraph Building

As mentioned earlier, Québec City had the telegraph system. The Great North Western Telegraph Company established in this building in 1856.

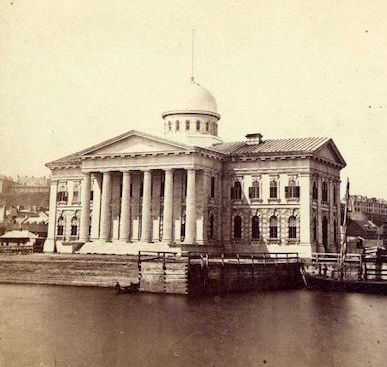

New Québec Custom House

The New Québec Custom House, dating back to the mid-19th century, reflects two realities of the time: the majority of the colony’s revenue comes from customs duties, and Québec City is a prosperous city that remains a significant Canadian port.

The current building has a different dome, an additional floor, and the river is located a bit further away.

Vanished Splendors: The Lost Architectural Heritage of 1866

Many buildings have been lost over time due to fires, changing needs, investments, and sometimes mistakes of the past. They now exist only in the archives.

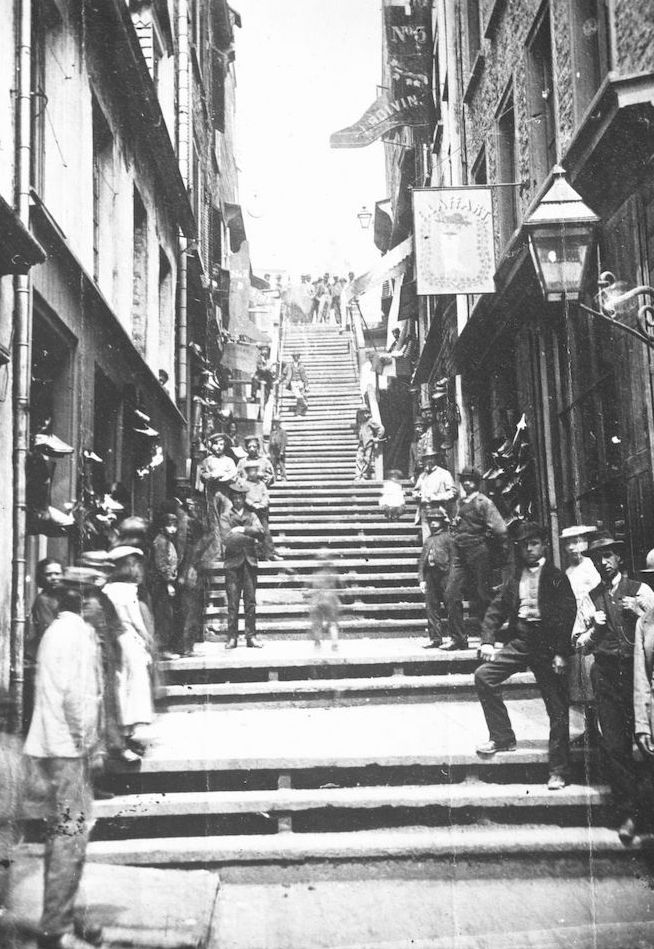

Former Breakneck Steps (Escalier Casse-Cou)

The Casse-Cou (Breakneck) staircase of that time lived up to its name even more so than today: it was narrower and had fewer landings. A fall down those stairs must have been particularly impressive.

This wooden staircase was replaced in 1893 by a magnificent iron structure designed by Charles Baillargé. The current staircase, however, dates back to the 1960s.

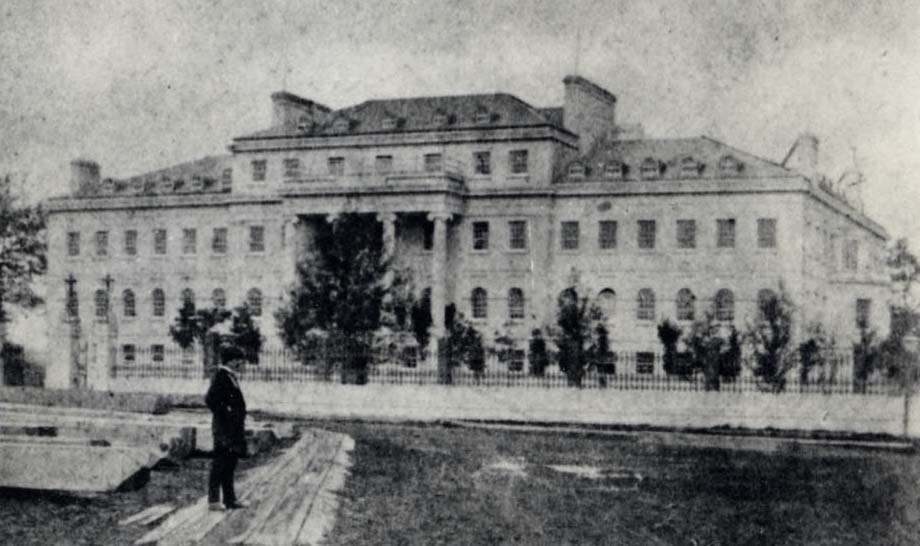

Marine Hospital

The Marine and Emigrant Hospital (Hôpital de la Marine et des Émigrés) of Québec City was active from 1834 to 1888. In 1832, during the cholera epidemic, there was an urgent need to provide medical care for immigrants arriving with sometimes contagious diseases. The hospital served as a complement to the existing health resources on Grosse-Île and its quarantine facilities.

The building changed its purpose over time and was eventually demolished in 1962.

Old Saint-Louis Gate

There is so much to say about the gates of Québec City! Here is the Saint-Louis Gate, photographed before its destruction, which was linked to the departure of the British troops. This gate had been built by the French before the Conquest.

Old City Hall

From 1842 to 1896, the municipal council held its meetings in the former residence of Major General William Dunn, located on Saint-Louis Street.

The building on the left, which can be seen in the picture, still exists today.

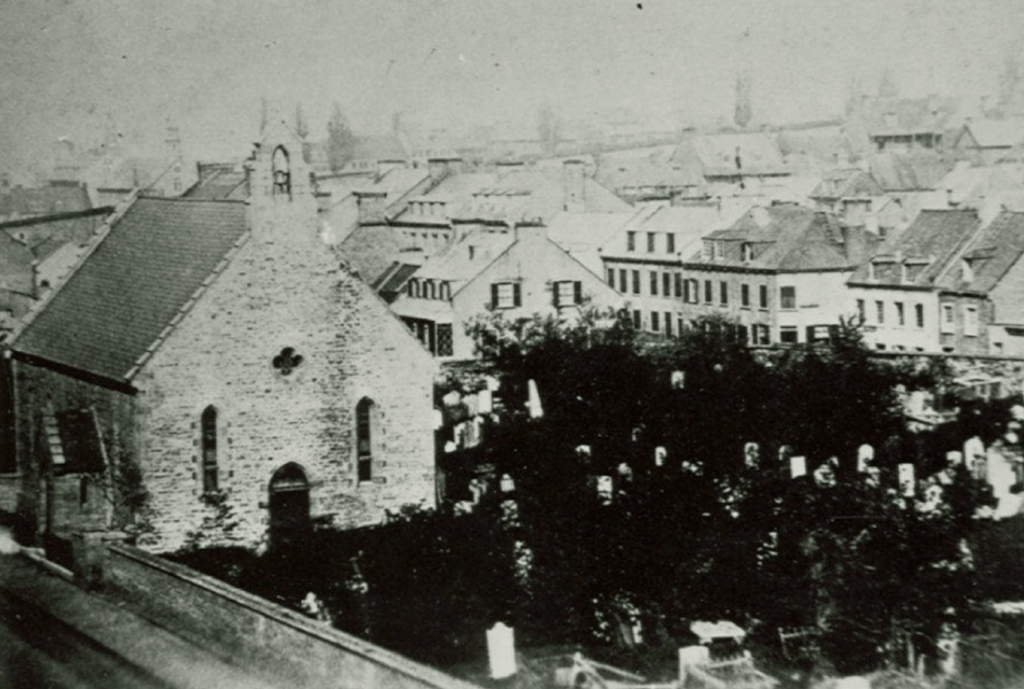

Sts Matthews chapel

One of the fires in 1845 had devastated the St. Jean neighborhood, including the wooden house of the gravedigger, which had been transformed into a chapel. A few years later, in 1849, a new chapel was built, this time made of stone. It was destroyed in 1875 to make way for the current church, which eventually was transformed into a library.

In the background to the right is now the Hilton hotel.

Jesuit College

The Jesuit College was one of the grand buildings of New France. Between the arrival and departure of the British army, it served primarily as a military depot and barracks. Abandoned, the building was demolished in the 1870s to make way for the Parliament. In reality, it was the City Hall that was constructed on the site.

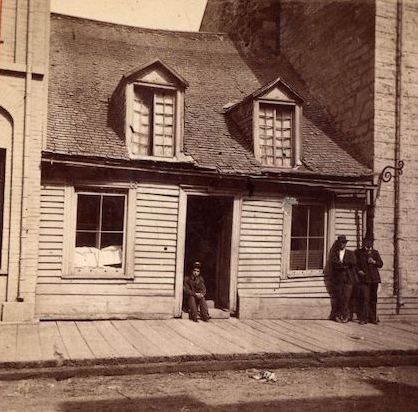

Montgomery House

It was in this humble house that the remains of General Montgomery were prepared in 1776 before being buried near the current Connaught Barracks. To commemorate the event, a plaque was placed on the existing building which has been constructed in 1890.

On the right, you can see a lantern bracket which is still existing.

Saint-Louis Hotel

The adventure of the Saint-Louis hotel began in 1852. In 1864-1865, the two houses that make up the hotel were merged, and two additional floors were added, giving the hotel its final appearance. General William Tecumseh Sherman stayed there at least in July 1866.

Despite its prestige and good reputation, it slowly declined until its closure in the 1960s.

The Saint-Louis Hotel was destroyed in 1969, and it was not until the end of the century that a new building emerged on the site: luxury condominiums Maisons de Beaucours.

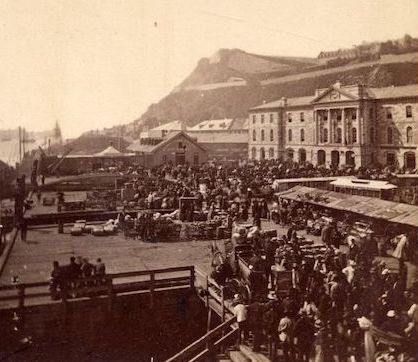

Marché Champlain

Ideally located at the heart of the economic hub of the time, this public market was active from 1860 to 1910.

In the photo, we can see a crowd in the foreground, the Champlain Market on the right, and in the background, the cliff and the Citadel.

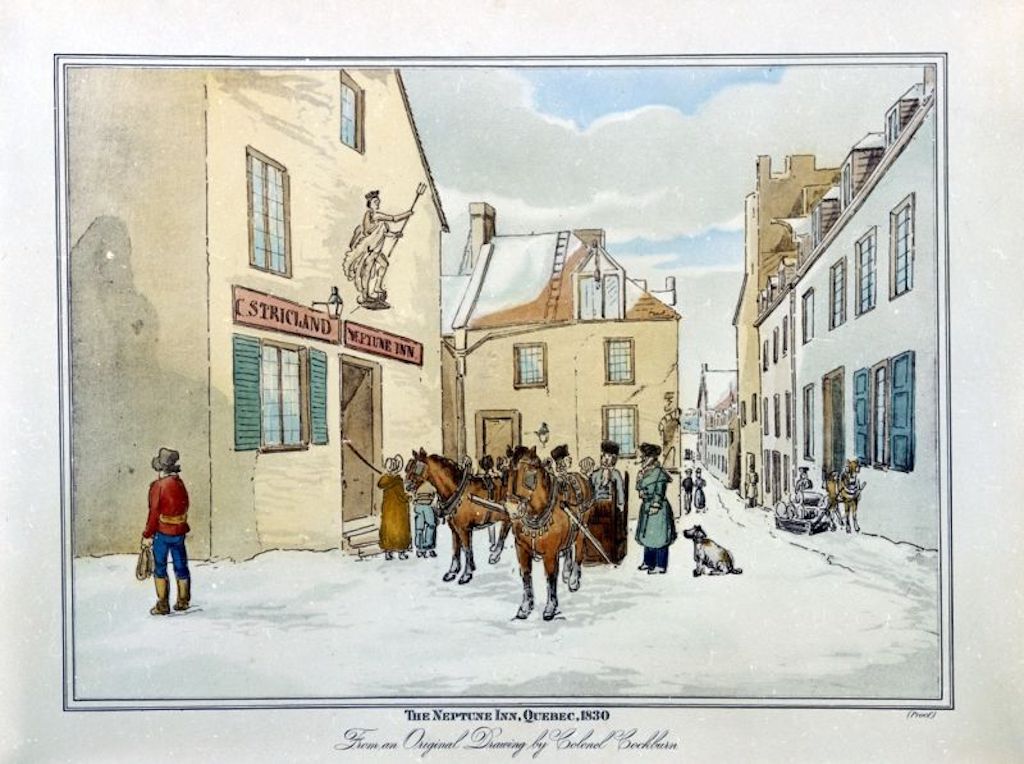

Neptune Inn

The Neptune Inn opened in 1809 and quickly became a gathering place for captains and merchants. Its facade was adorned with the figurehead of the ship Neptune after it sank in 1817. However, it disappeared around 1870. Three decades later, a sculpture of Neptune, created by Louis Jobin, was installed. You can now admire this sculpture at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

Old parlement

The first Parliament building was located on the site of the current Parc Montmorency but burned down in 1854, just two years after its inauguration. Some of the stones from the building were salvaged and used to construct the Champlain Market. The Assembly and Legislative Council temporarily relocated to various buildings. It was not until 1860 that the elected officials began meeting in the second Parliament building, which unfortunately was destroyed by fire in 1883.

At the forefront, we can see the snow-covered roof of the Prescott Gate, and in the background on the left, the Camille-Roy Pavilion with its flat roof. Finally, towards the right in the background, we can catch a glimpse of the customs building with its original dome. These are all clues that help in dating the photo.

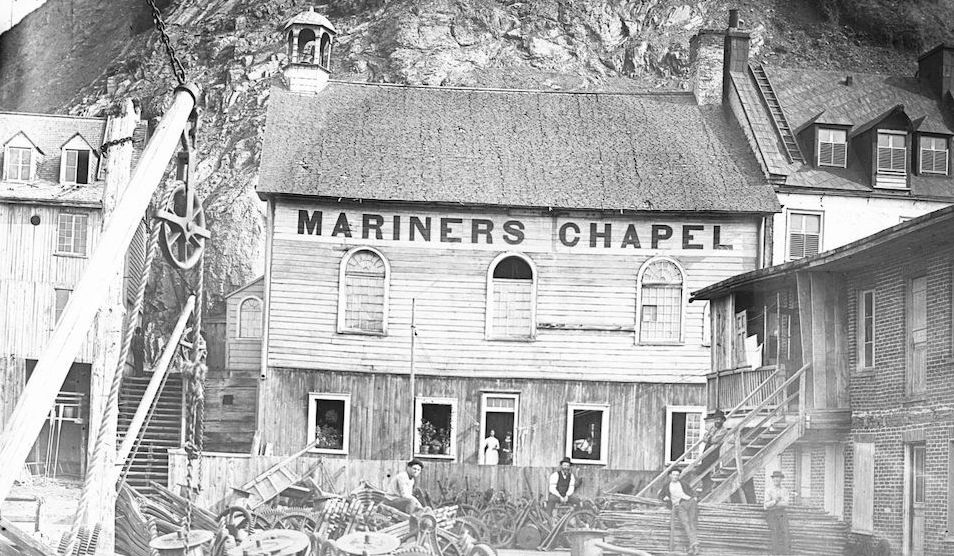

Mariners Chapel

Founded in 1847 by the Anglicans, the Mariners Chapel still exists today, although it is no longer affiliated with a particular religion.

Originally, it provided various services, including religious services, to English sailors, as well as sailors of other nationalities later.

Glimpses of the Victorian Era: Uncovering Lévis’ Past

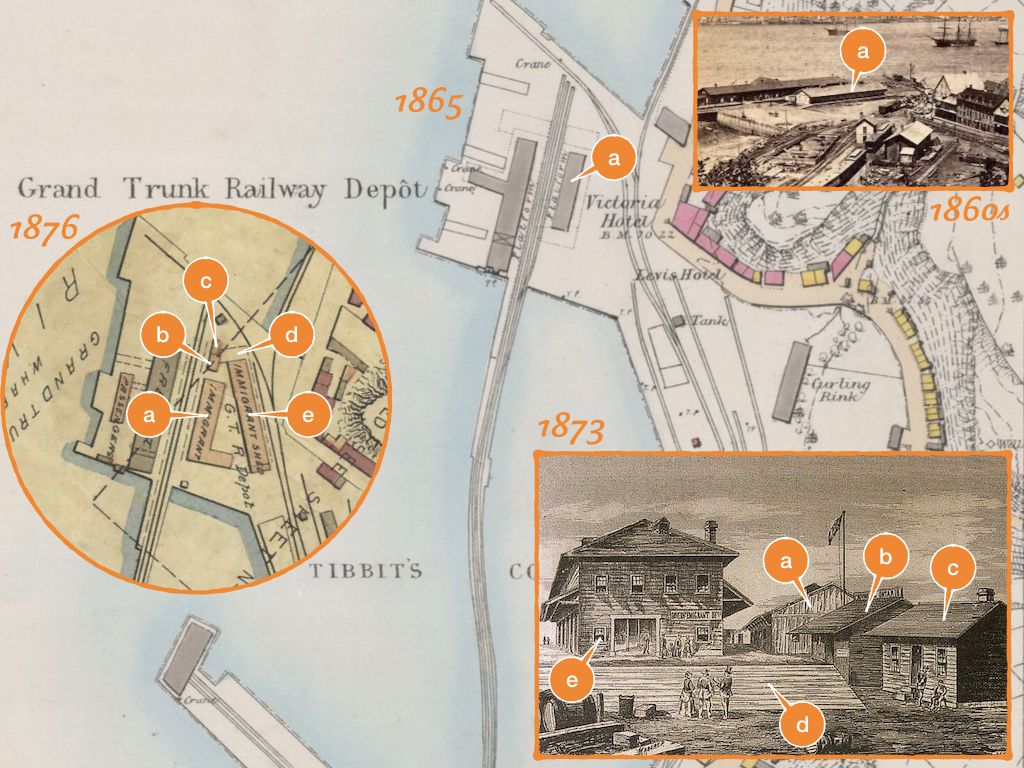

You probably already know that I guide in Lévis, and Robin’s request has fortunately prompted me to delve into the case of Lévis. Indeed, she specifically asked me to conduct my research on Québec City, with a focus on the train station, as her ancestors may have taken the train. However, in 1866, Québec City did not have a train station. Since 1854, it was located on the other side of the river, in Lévis, in the area of Tibbits’ Cove.

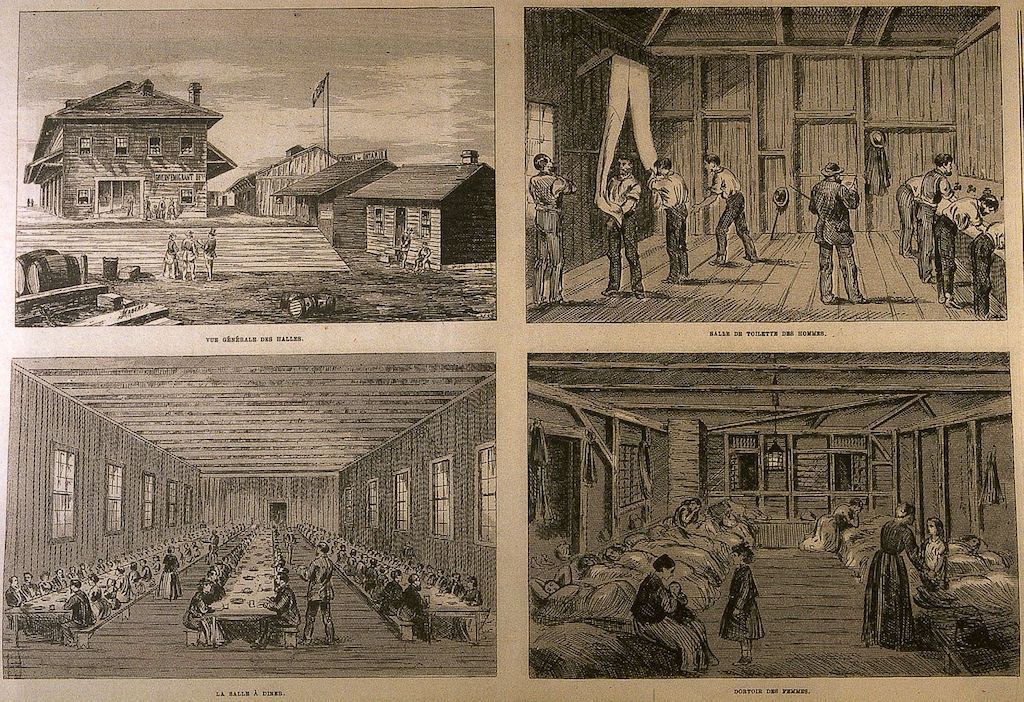

In 1866, a total of 28,648 immigrants passed through Québec City and Lévis, while the overall population of Lévis County was below 25,000. Up to 90% of immigrants would actually land in Lévis, sometimes labelled as “Québec South”, rather than Québec City itself. Even after the arrival of the train in Québec City in 1879, Lévis would remain a significant landing place.

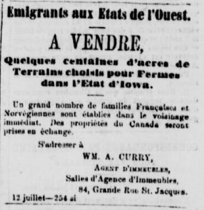

Among them, a fraction will settle, at least temporarily, in the surrounding areas. The overwhelming majority of them will head west. In fact, various recruiters were active in the sector, enticing this clientele eager for opportunities.

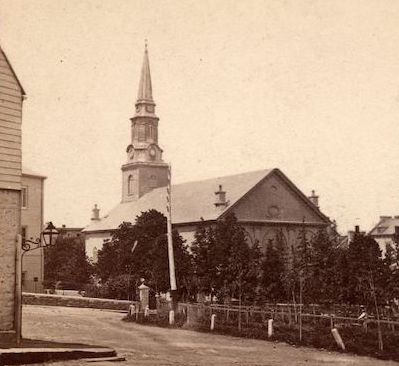

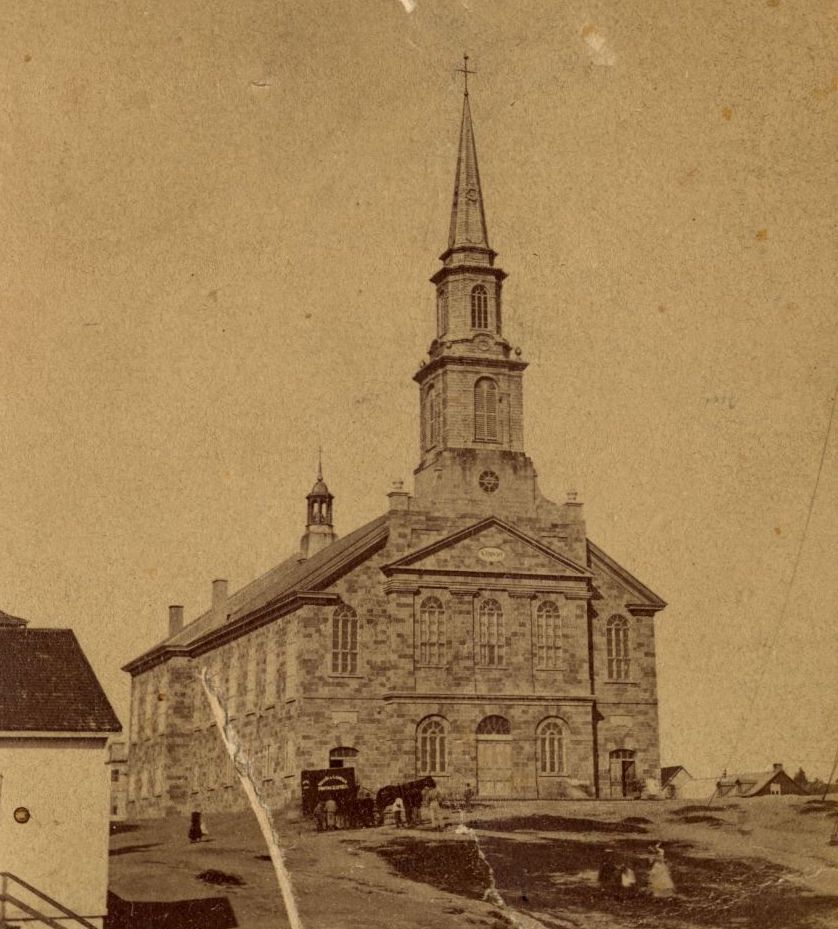

Notre-Dame-de-la-Victoire Church

Built and expanded in the 1850s, the Notre-Dame-de-la-Victoire Church is a prime example of neoclassical architecture. At the time, it was one of the largest churches in the country, standing amidst only a few surrounding houses.

The origin of the building and the parish perfectly aligns with the context of the time: population and economic growth, the arrival of the train in the area, and, of course, the political and social tensions between French-Canadians and Anglo-Canadians.

It wasn’t until 1957 that the clock was installed on the church’s steeple. It comes from the post office, which was previously located in the area near the ferry.

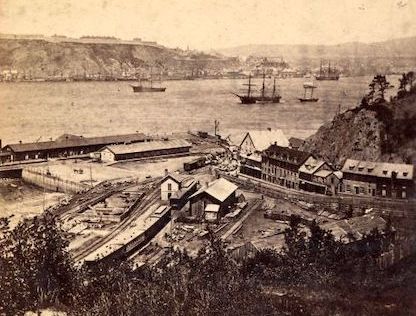

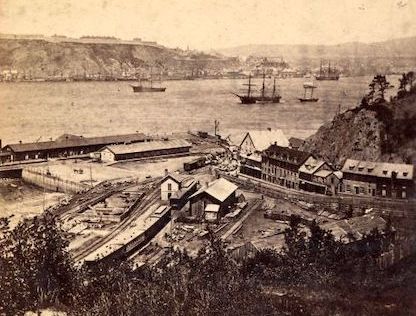

Tibbits’ Cove: First Victoria Hotel and Grand Trunk Railroad

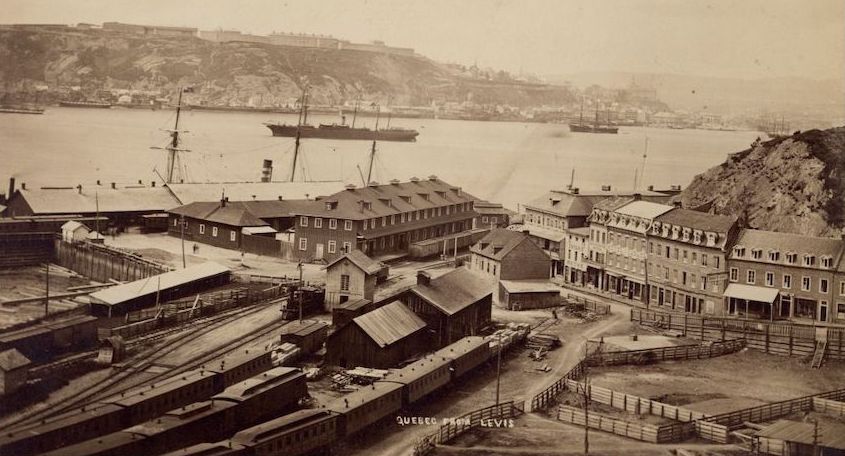

As part of this research, exploring the environment that Robin’s Norwegian immigrant ancestors experienced, this picture holds the utmost importance.

It is highly likely that her grandmother passed through there. Indeed, it was in the area of Tibbits’ Cove where Norwegian immigrants boarded the train to head West, as the Grand Trunk station was located there. It was also the place where some of them waited, as the immigrant shed was situated there as well.

In the archives, the photo is dated from the 1870s. But check the tall building with a bright roof located at the corner at the foot of the cliff: it is the Victoria Hotel before it burned in August 1867.

Comparing with the second picture, we can see the remaining parts of the Victoria Hotel as they still exist today (although perhaps not for much longer).

You can find on BAC-LAC two interesting pictures of Tibbits’ Cove before 1865, here (not the Hadlow Cove) and there.

Norwegian Immigration in 1866: A Gateway to the West

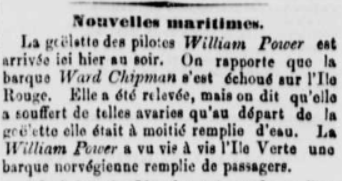

1866 appears to be the first year when a massive arrival of Norwegian immigrants is observed in Québec City area. These immigrants had the goal of heading westward. They stayed in the old capital for a few days before continuing their journey. The newspapers of the time provide evidence of this, with dispatches mentioning the arrival of ships, articles describing these new arrivals, and advertisements for the West.

The political context was quite particular, as the colonial authorities were alarmed by the attacks of the Fenians who were conducting raids in Canada. The largest confrontation actually took place less than two weeks before the arrival of the Askur (which arrived on June 13, 1866 with Robin’s ancestors): on June 2, the Battle of Ridgeway occurred, pitting around 600 Fenians against 850 Canadian soldiers in the vicinity of Niagara. Although the Fenians eventually returned to the United States where they were disarmed, tensions persisted high and the Province of Canada remained on high alert.

Excerpts and Transcriptions of Noteworthy Articles and News Pieces

Currently, there are approximately 4,000 Norwegian emigrants in the port of Quebec, awaiting the time when they can depart via the Grand Trunk Railway to the West.

Le Journal de Québec, 13 juin 1866

Out of this number, around 1,200 to 1,500 take shelter in the temporary accommodations set up at the Quebec- South station, while the others remain on the ships that brought them here.

During the day, they can be seen moving around the streets of the city in large groups. Their healthy appearance and clothing indicate a class of emigrants that is more than ordinary.

According to reliable information we have received, the number of Norwegian emigrants who have passed through the port of Quebec since the opening of navigation, mostly to reach the United States, is 11,000, and an equal number is expected during the course of the summer.

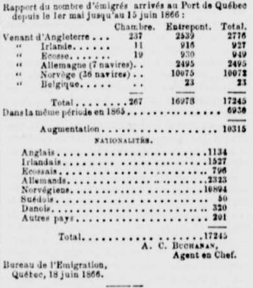

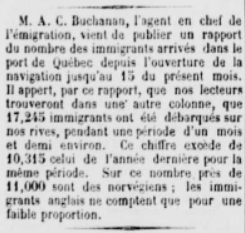

Mr A. C. Buchanan, the chief emigration agent, has just

Le Journal de Québec, 19 juin 1866

published a report on the number of immigrants who have

arrived at the port of Quebec since the opening of navigation

until the 15th of this month. According to this report, our readers will find in another column that 17,245 immigrants have been disembarked on our shores during a period of approximately one and a half months. This figure exceeds last year’s count for the same period by 10,315. Out of this number, nearly 11,000 are Norwegians, while English immigrants account for only a small proportion.

Emigrants to the Western States. FOR SALE, A few hundred acres of carefully selected land for farms in the state of Iowa. A large number of French and Norwegian families have settled in the immediate vicinity. Canadian properties will be accepted in exchange. Please contact WM. A. Curry, real estate agent, Salles d’Agence d’Immeubles, 84, Grand Rue St. Jacques.

La Minerve, 17 juillet 1866, Le Pays 26 juillet 1866 and many other newspapers

Robin’s tours

Exactly 156 years, 11 months, and 25 days after the docking of the Askur in Québec City with Christina Birte Solum and her family, I had the pleasure of guiding Robin and her husband through Old Québec and Lévis. We thoroughly explored both the Upper and Lower Towns of this UNESCO world heritage site. It was an opportunity to offer them a personalized private tour, delving into various aspects of local history, visiting the must-see attractions as well as uncovering hidden gems off the beaten path. Our focus, of course, centered heavily on the year 1866. During our time in Lévis, we dedicated most of our visit to Tibbits’ Cove, where the train station and immigrant shed once stood, meticulously detailing the locations of the buildings depicted in archive pictures.

I cannot say enough about the diligence, insight and enthusiasm Xavier showed in helping me research the history of my Norwegian ancestors’ immigration to Quebec. My initial email contained a formidable request; “I am looking for someone to help me identify the buildings my grandmother would have seen when her ship landed in Quebec in 1866 and find photographs of the city and port from that period.” Xavier responded immediately and within a few days had provided me with what became the foundation of my understanding of her travel experience. He sent me copies of historical images and newspapers from that time and, when we met, was able to take me not only to the relevant sights in Quebec but also in Levis.

In addition to being a very nice person and exceptional researcher, Xavier is an excellent guide to the general history of Quebec. He loves history and it shows. We could not have met our objectives for our trip without his guidance and support.

Robin Boger on Google Review

Experiencing the Charm in Person

These photos are truly stunning and allow us to travel through time, offering a unique opportunity to admire buildings that no longer exist. Since 1866, the city has undergone significant transformations, but it has also successfully preserved its undeniable charm and at least part of its heritage. I wholeheartedly encourage you to visit Québec City and Lévis, and experience their captivating essence firsthand.