It was a beautiful September day, and I was guiding a private group of cruise passengers—Margaret, Scott, Zoe, and Bob—around the iconic Château Frontenac. As we strolled along the Dufferin Terrace, Zoe’s gaze fell upon the château’s windows, adorned with coats of arms. Curious, she asked who these crests represented. I was able to identify a few, but others remained a mystery.

As a tour guide, I always strive to provide precise answers, so when I encounter questions like this, I make it a point to research and follow up with my clients later. What better way to share these discoveries than through an article that unveils the stories behind these crests? Join me as we explore the rich history captured in glass and unravel the tales they silently tell.

Unveiling the Heraldry: Tracing the Legacy of New France

My investigation led me to a key source: “Armorial du Canada français” by Edouard Zotique Massicotte and Régis Roy, published in 1915. This book provided invaluable insights into the heraldic symbols displayed on the château’s windows. Each emblem represents a key figure from New France—officers, colonial administrators, governors, and other influential personalities. I also consulted “Armorial des principales maisons et familles du royaume” by Pierre-Paul Dubuisson, published in 1757, which illustrates the coats of arms of the era’s most prominent noble families of the French Kingdom. Unsurprisingly, it includes crests connected to Canadian history.

The colors of the stained-glass windows are not always accurate, with some differing from the original heraldic symbols. These inaccuracies add an element of mystery, as they sometimes make it unclear which coat of arms is being represented.

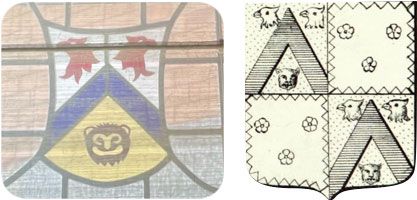

Liénard de Beaujeu

The first coat of arms was the most challenging to identify, as it is not depicted in the two primary sources I consulted for my research. After some exploration, I found that it likely belonged to the Liénard de Beaujeu family, based on the work of Abbé François Daniel.

The Liénard de Beaujeu family, a French noble lineage, established itself in Canada in 1697. Unlike most Canadian nobility of provincial origins, Louis Liénard de Beaujeu belonged to the court nobility, serving in Versailles before moving to New France. His descendants played significant roles in New France history, with some settling in France and others remaining in Canada post-British cession.

Daniel-Hyacinthe-Marie Liénard de Beaujeu died in 1755 during the Battle of Monongahela against the British.

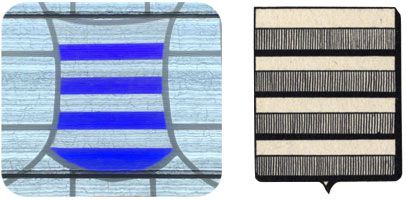

Brisay de Denonville

Denonville’s coat of arms should feature alternating white and red stripes. However, the stained-glass window displays it in white and blue, indicating an error in its depiction.

Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville (1637–1710) was the Governor General of New France from 1685 to 1689. A military man with a distinguished career in the French army, he was appointed to strengthen the colony and counter the growing threat from the Iroquois and English interests. Denonville implemented several reforms, focusing on improving the colony’s defense, curbing abuses in the fur trade, and strengthening relations with Indigenous nations allied with the French. Despite some military setbacks, including the controversial attack on the Seneca and the Iroquois’ raid on Lachine, Denonville’s efforts laid the groundwork for future governors to fortify New France.

He was the first governor to attempt serious social reforms in the colony, believing that Canadian society needed to channel the energy of its youth.

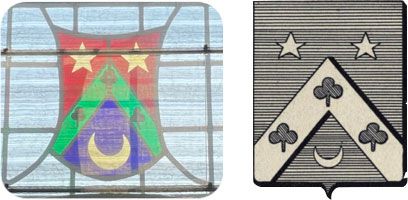

Raudot

Raudot’s coat of arms should feature a blue background, silver elements, and a chevron with green clovers. However, the stained-glass window inaccurately depicts the coat of arms in red, green, and blue.

Jacques Raudot (1638–1728) served as the intendant of New France from 1705 to 1711. A skilled magistrate with extensive legal experience, Raudot was known for his dedication to reforming the colony’s institutions. During his tenure, he focused on improving public order, justice, and the seigneurial system, issuing numerous ordinances and advocating for education in rural areas. He aimed to reduce the power of wealthy interests, like merchants and seigneurs, in favor of the common habitants. Although his strong-willed and sometimes abrasive nature led to conflicts, particularly with Governor Vaudreuil, Raudot’s contributions provided valuable insights into the colony’s social and economic challenges.

Despite his advanced age when he arrived in New France, Raudot was known for his lively social gatherings and his interest in music, even hosting concerts in the intendant’s palace.

Antoine-Denis Raudot (1679–1737), intendant of New France from 1705 to 1710, was an influential economic theorist. He proposed making agricultural products, rather than furs, the colony’s economic foundation and envisioned Cape Breton as a central hub for trade. Raudot worked to improve internal commerce, agriculture, and relations with the colony’s habitants. Despite his efforts being hindered by war and conflicts with Governor Vaudreuil, his ideas laid groundwork for future French colonial policies, including the development of Louisbourg. Later, he became a key figure in French colonial administration and economics.

Antoine-Denis Raudot died at Versailles and left most of his fortune to his domestics. This act was quite unusual for someone of his status at the time and reflects a unique aspect of his character.

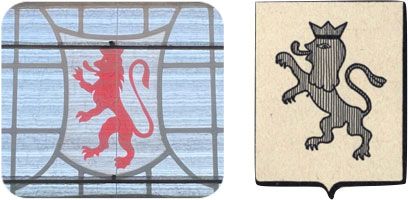

Rigaud de Vaudreuil

Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil (1643–1725) served as the Governor of Montréal before becoming the Governor General of New France from 1703 to 1725. He played a key role in defending the colony against English incursions and maintaining alliances with Indigenous nations. His long tenure is marked by his efforts to strengthen the colony’s defenses and expand French influence in North America.

Despite his noble status, Philippe was known for his deep understanding of Indigenous cultures and languages. He often dressed in Indigenous attire during diplomatic meetings, which earned him a unique level of respect and trust among Indigenous nations.

Son of Philippe, Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil (1698–1778) was the first Canadian-born Governor General of New France, holding office from 1755 until the fall of the colony in 1760. He managed the defense of the colony during the War of the Conquest (Seven Years’ War; French & Indian War), ultimately signing the capitulation of Montréal to British forces, which marked the end of French rule in Canada.

Being born in Canada made him particularly committed to defending the colony and its people, as he saw New France not just as a French territory, but as his homeland.

Lévis

François de Lévis (1719–1787) was a distinguished French military officer who played a key role in the defense of New France during the War of the Conquest (Seven Years’ War; French & Indian War). As the second in command to the Marquis de Montcalm and later as commander of French forces in North America, he displayed remarkable leadership and strategic acumen, notably during the Battle of Sainte-Foy in 1760, where he led French forces to a significant victory against the British. Following the capitulation of Montréal, he returned to France, where he was eventually promoted to Marshal of France, a testament to his military prowess and dedication.

Despite the tumultuous wartime relations, Lévis and his former adversary, James Murray, the British commander at Québec City, developed a cordial friendship post-war, often corresponding and helping each other when possible.

The best scenic view of Old Québec and the Château Frontenac is from across the river in Lévis, a city named after this victorious general.

Lefebvre de la Barre

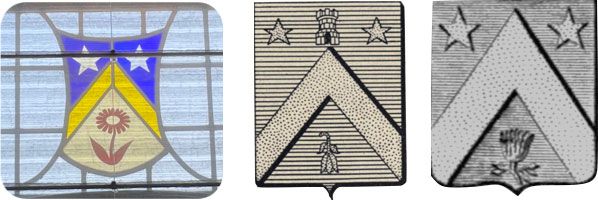

On the stained glass at Château Frontenac, the background is partly blue (correct) but also pale yellow (incorrect). The chevron is golden, and the two white stars are present, but the tower is missing. The flower is not depicted as in Massicotte and Roy’s work; however, it resembles the one described by Dubuisson, which has no tower, casting doubt on whether this truly represents Lefebvre de La Barre

Joseph-Antoine Le Febvre de La Barre (1622–1688) served as governor-general of New France from 1682 to 1685. Despite a long military and administrative career, his tenure in New France was marked by failed policies, including unsuccessful military campaigns against the Iroquois and conflicts over trade. He faced criticism for his dealings with Indigenous allies and his apparent focus on personal gains. Ultimately, his actions contributed to the tensions in New France that followed his departure in 1685.

La Barre served as governor of Guiana before moving to Canada, experiencing an extreme change in climate.

Frontenac

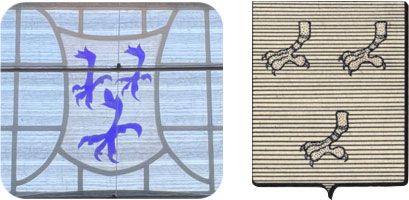

The coat of arms should have a blue background with three gold griffin claws. However, on the stained glass, it features a white background and blue claws. Despite this inaccuracy, the placement of this crest in the central window of the dining room strongly indicates that it belongs to Frontenac.

Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac (1622–1698) served as Governor General of New France twice, from 1672 to 1682 and 1689 to 1698. He defended the colony against the Iroquois and English, notably during the Siege of Québec City in 1690. Known for his strong leadership, he developed the fur trade, expanded fortifications, and established alliances with Indigenous peoples. Despite conflicts with the church and other officials, Frontenac is celebrated for preserving French interests in North America.

Frontenac was known for his bold and defiant nature, as demonstrated during the 1690 siege of Québec City, where he famously responded to an English demand for surrender with, “I have no reply to make to your general other than from the mouths of my cannons.” The Château Frontenac is named in his honor.

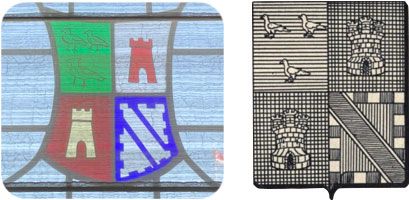

Bégon

The background should be blue, with a gold chevron, two gold roses, and a gold lion. However, on the stained glass window, the design deviates significantly: it has a yellow top background and white bottom, a green chevron, a red lion, and only the roses match the original description in color, as they are yellow.

Michel Bégon de La Picardière (1667-1747) served as the intendant of New France from 1712 to 1726. He significantly improved the colony’s economy by developing the lumber industry and regulating the fur trade. He also implemented policies to encourage agriculture and infrastructure development, contributing to New France’s growth.

Bégon was passionate about botany and horticulture, introducing various plant species to the colony, including the begonia flower, which was named in his honor.

Lévis-Ventadour

Henri de Lévis, Duc de Ventadour (1596–1680) served briefly as the Viceroy of New France from 1625 to 1627. His most notable contribution was promoting missionary work in Canada by sending Jesuit missionaries to the colony, aiming to convert the Indigenous peoples to Christianity. His efforts laid the groundwork for the French Catholic presence in New France, shaping its cultural and religious landscape for years to come.

Pointe-Lévy, named by Samuel de Champlain in honor of Henri de Lévis, is now home to the Davie Shipyard and is visible from the Château Frontenac.

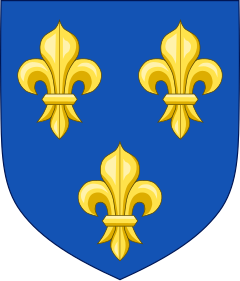

Razilly or French Kings

This stained glass coat of arms presents two possible interpretations. If the background is correctly blue, the fleurs-de-lis should be gold, representing the kings of France. However, if the fleurs-de-lis are accurately depicted in white, then the background should be red, representing Razilly, who is more associated with Acadia than Canada. Given the artistic liberties taken with the colors in the glass, both options will be briefly presented, leaving the final interpretation to the reader.

Isaac de Razilly or Rasilly (1587–1635) was a French naval captain and governor of Acadia. He led the re-establishment of French control in Acadia in 1632 and focused on developing a permanent colony, promoting agriculture, trade, and cooperation with Indigenous peoples. Razilly laid the groundwork for the future Acadian population by settling families in the region.

Claude de Launay-Razilly (1593–1654), brother of Isaac, played a key role in Acadia’s early colonial administration. As an administrator of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, he oversaw trading interests, particularly in the fur trade, which was vital to the colony’s economy. After his brother’s death, Claude managed their family interests in Acadia from France.

François I laid the groundwork for exploration in North America by supporting Jacques Cartier’s voyages. Henri IV initiated a permanent French presence by backing early settlements. Expansion efforts continued under the regency of Marie de Medici. Under Louis XIII, the Compagnie des Cent-Associés was established in 1627, introducing the seigneurial system. During Anne of Austria’s regency, colonization efforts persisted. Louis XIV reinforced control with the Sovereign Council. Though initially supportive, Louis XV’s reign faced constraints, leading to New France’s decline and eventual loss to Britain.

The French colonial administration generally maintained the colony’s economic dependence on the metropole, emphasizing the export of raw materials to France. Additionally, French authorities often prioritized establishing and maintaining alliances with Indigenous nations, which were crucial for trade, military support, and expanding territorial claims. This approach set New France apart from other colonial powers of the time.

Montcalm

The stained-glass interpretation leaves no doubt about its identity due to its complex and unique design. However, the chosen colors on the glass are far from accurate.

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm (1712–1759) was the commander of French forces in North America during the War of the Conquest (Seven Years’ War; French & Indian War). He led key battles, including the defense of Québec City, and played a significant role in early French victories. Despite his strategic efforts, he ultimately faced defeat at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, marking the fall of the capital of New France.

A few years ago, Montcalm’s remains were moved from the Ursuline Chapel to the cemetery of the Hôpital Général, so he could rest alongside his soldiers.

Talon

While the colors on the window do not perfectly match this description, the distinctive design leaves no doubt about its identity.

Jean Talon (1626–1694) was the first intendant of New France to arrive in Canada, serving from 1665 to 1672. He significantly contributed to the colony’s development by diversifying its economy, promoting agriculture, trade, and encouraging immigration to boost the population. Talon initiated infrastructure projects, including mills and shipyards, aiming for a self-sufficient colony rather than complete reliance on France.

Jean Talon did order the establishment of a brewery in New France. He saw it as a way to encourage the production of local resources and reduce dependence on imported goods, particularly imported alcohol like wine and brandy from France.

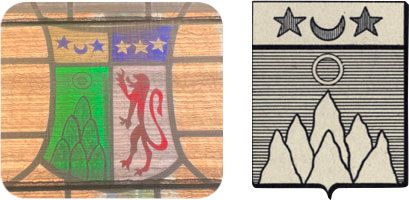

Jonquières

The attribution of this coat of arms is uncertain, as it is unclear which family it represents. It consists of two parts. The dexter side features a unique design with mountains, an annulet (ring), two stars, and a crescent, matching the arms of Jonquières, though the colors are incorrect. However, I have been unable to identify the sinister side. In the absence of a better match, let’s talk about Jacques-Pierre de Taffanel de La Jonquière!

Jacques-Pierre de Taffanel de La Jonquière (1685–1752) was a French naval officer and colonial administrator who became the governor of New France in 1749. His tenure focused on defending French interests against British encroachments in North America, particularly in the Ohio Valley. Despite his efforts, his health declined, and he passed away in office.

La Jonquière was a seasoned naval officer with a long career, including involvement in the War of the Austrian Succession, during which he was captured by the British.

A Moment of Reflection: History in Every Crest

In conclusion, the stained-glass windows of the Château Frontenac provide a captivating glimpse into the legacies of New France’s historical figures. While the heraldic symbols may not always match their original colors, they encapsulate the spirit of their era. You can reflect on these stories while dining in the Champlain salon, where the crests adorn the dining room windows, adding a layer of historical ambiance to the experience.

Passionate about history? Our private, customized tours immerse you in the rich heritage of Québec City, New France, and beyond. Discover iconic sites, go off the beaten path, and learn fascinating stories tailored to your interests. Book your unique experience today or contact us for more information!