Old Québec is a city rich in history and architecture, and its gates are a testament to its past. From the strong and thick gates that once protected the city, to the ornate structures that now serve as romantic symbols, the gates of Old Quebec have played a vital role in the city’s history. In this article, we will take a journey through time and explore the history, purpose, and evolution of Old Quebec’s gates, delving into the stories behind the gates that no longer exist and the ones that still stand today.

The Evolution of Old Quebec’s Gates: From Defense to Decoration

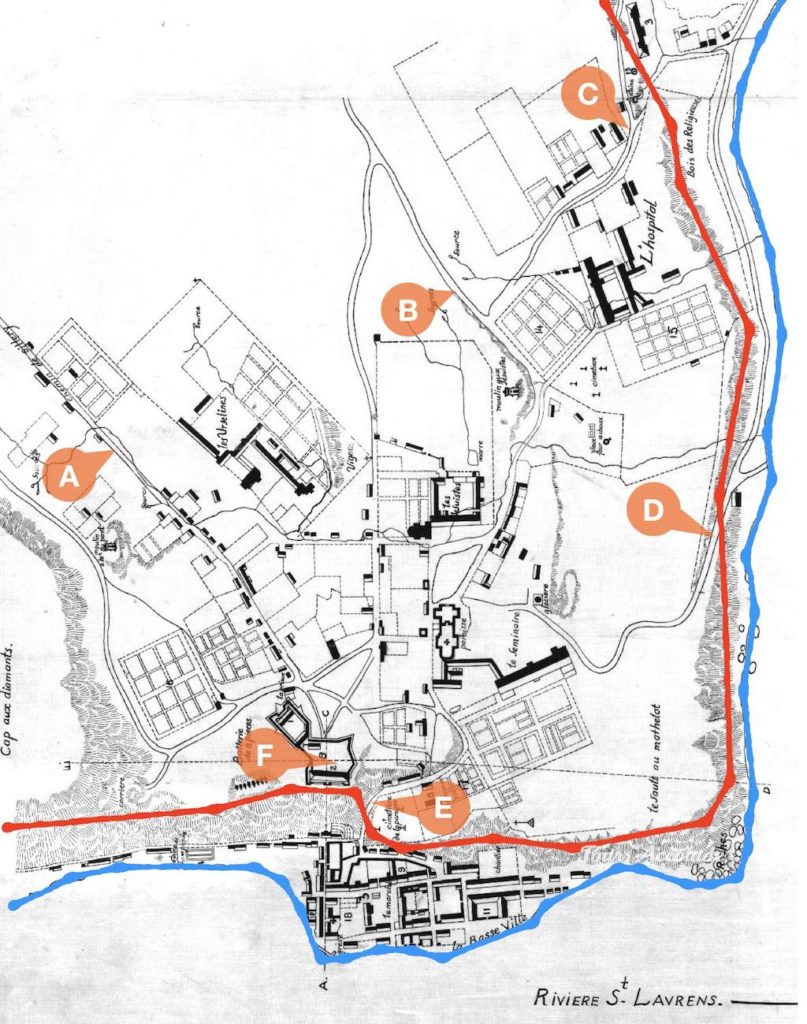

Quebec City was founded in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain as a fur trading post. At the time, the post had no proper fortifications and relied on its location and the strength of the post itself to protect its valuable trading goods.

Protecting the town against the British

It wasn’t until 1690, under the governorship of Louis de Buade de Frontenac, that a temporary palisade was built.

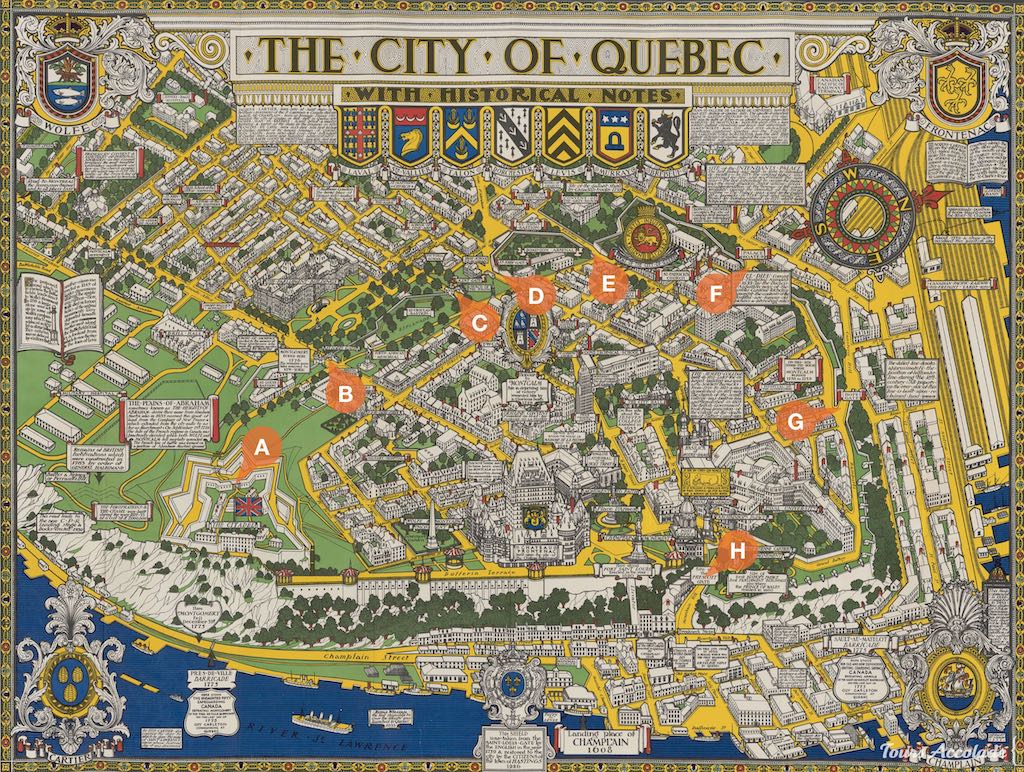

As the threat of the British in New France grew, the need for proper fortifications able to withstand cannon fire became increasingly pressing. In the 1690s and again in the first half of the 1700s, French authorities began building thick walls spanning the entire width of the U-shaped cliff, effectively enclosing the vulnerable plateau within a protective barrier. Gates have been built to control access in and out of the city and batteries to protect the shore.

In the Lower Town, now known as Petit Champlain and Old Port, the area was not heavily fortified at the time, except with batteries. It was seen as challenging for enemies to disembark and too small to maneuver large numbers of troops to reach the Upper Town. The narrow passages in the cliff are also natural obstacles in their own right. As a result, the French did not feel the need to allocate resources towards building permament gates in that area.

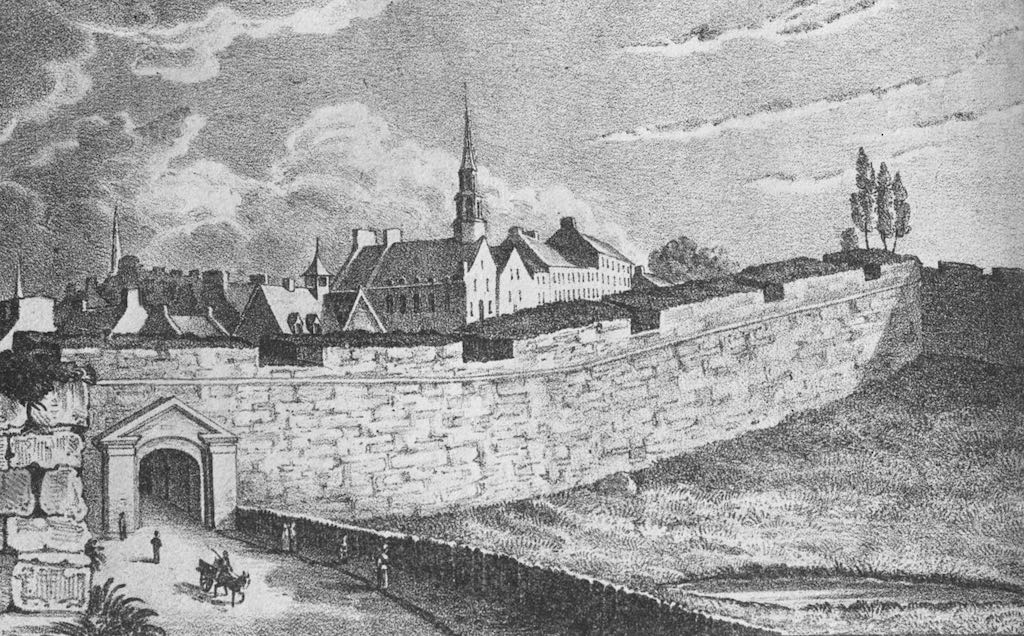

These gates were designed for practicality, with little embellishment, and were narrow to facilitate closing for protection. They had a guardhouse (corps de garde) above or nearby. It is an essential feature for the soldiers, particularly during the winter.

Posterns are secondary gates that are smaller and less heavily fortified, used for flanking an enemy near a main gate or discreetly exiting the walled city.

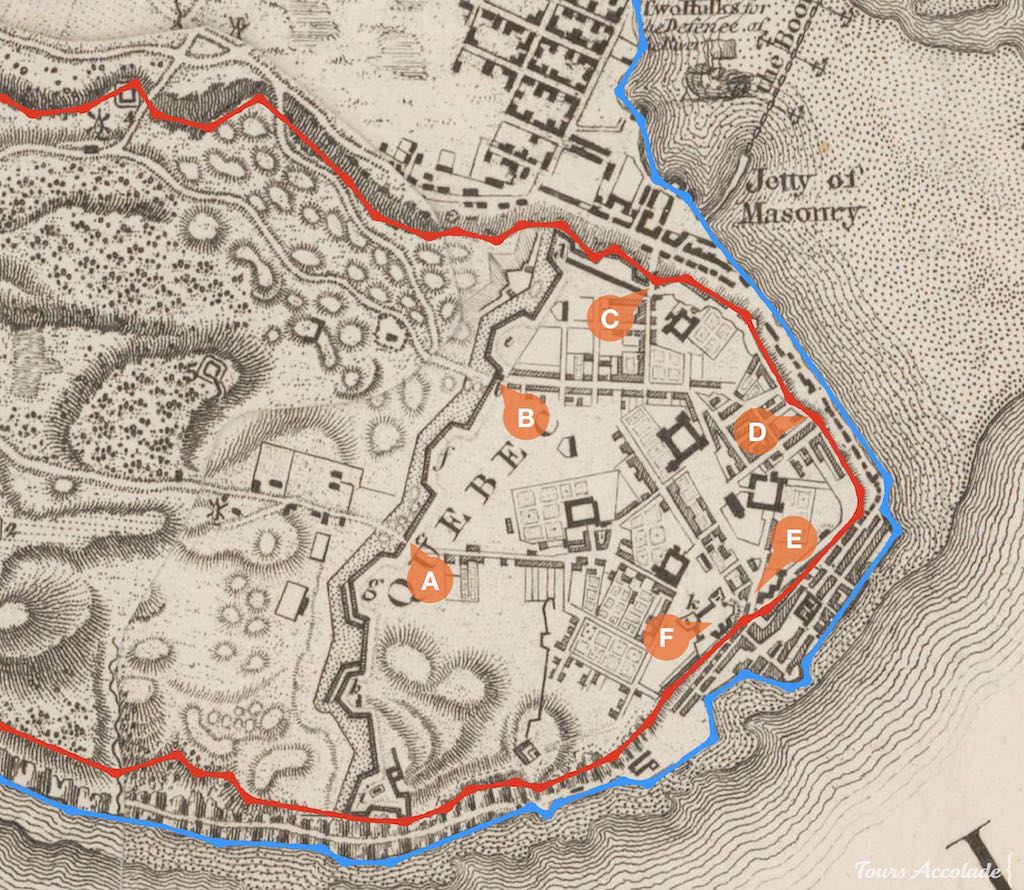

In the 1760s, France lost the Seven Years War (also known as the French & Indian War, and The Conquest) and was forced to cede Canada to the British Crown. The fortifications were briefly abandoned for a period of time.

Protecting the city against the Americans

In response to the failed attempt by Benedict Arnold to capture Quebec City in 1775-1776 and recognizing the ongoing threat from the Americans, the British chose to retain, upgrade and expand the city’s defensive network, which included fortifications above the cliff with new gates, the construction of the Citadel a few years after the War of 1812 and more.

As the city grew in the 1800s, pressure from the people and merchants increased to open the old city to the new suburbs. British authorities tried to find a compromise.

Nevertheless, the gates were closed every night, effectively separating the Upper Town within the walls from both the Lower Town and the surrounding faubourgs (suburbs).

Protecting the charm of the city

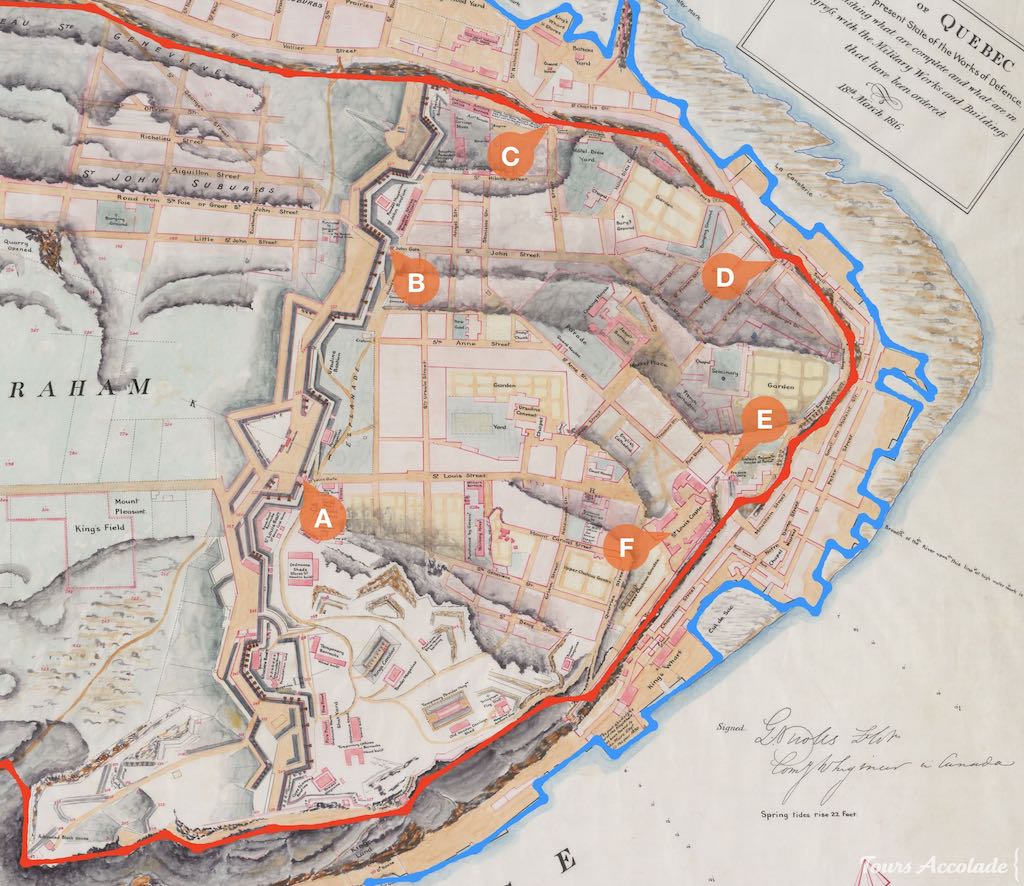

In 1867, Canada officially became an independent country and the British army left Canada and Québec City. As the American threat decreased and artillery technology advanced, the old fortifications were considered obsolete and no longer necessary. Municipal authorities began demolishing the gates and parts of the main wall to accommodate the increasing traffic.

Fortunately, the Governor General of Canada at the time, Lord Dufferin, convinced the city council to preserve the fortifications. In doing so, the city kept most of the wall and built new, larger gates that were designed for the traffic but not for defense, which now serve as iconic parts of Old Quebec’s identity.

The ornate, romantic gates have now tiny fake decorative guardhouses, which now serve primarily as small storage rooms.

Gone but not Forgotten: The Demolished Gates of Old Quebec

As the fortifications expanded or their purpose changed over time, many gates have been destroyed. Now, only old paintings and photographs remain as a record of their existence.

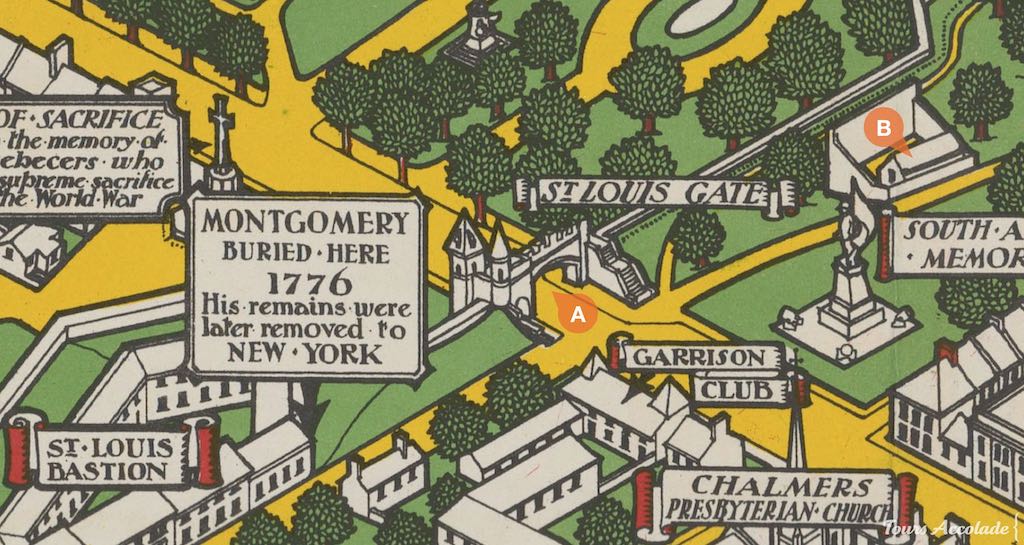

Saint-Louis Gates (1690s-1740s-1870s)

The first Saint-Louis Gate was built in the 1690s by Jean Le Rouge and Pierre Janson dit Lapalme. It was part of the main wall of the time, which did not include the hill where the citadel now stands.

To include this higher ground within the city wall, Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry built a new wall in the mid 1740s, amid increasing tension between the French and British empires. The previous fortifications and gates were demolished and new ones were constructed closer to the Plains of Abraham, significantly expanding the size of the Upper Town.

This second French Saint-Louis Gate, however, was torn down in 1871 as it was considered too narrow and outdated to accommodate the growing traffic demands.

Saint-Jean Gates (1690s-1740s-1860s)

The first Saint-Jean Gate has a similar timeline as the Saint-Louis Gate: it was first built in the 1690s, destroyed and rebuilt at a new location in the 1740s, following the expansion of the fortifications.

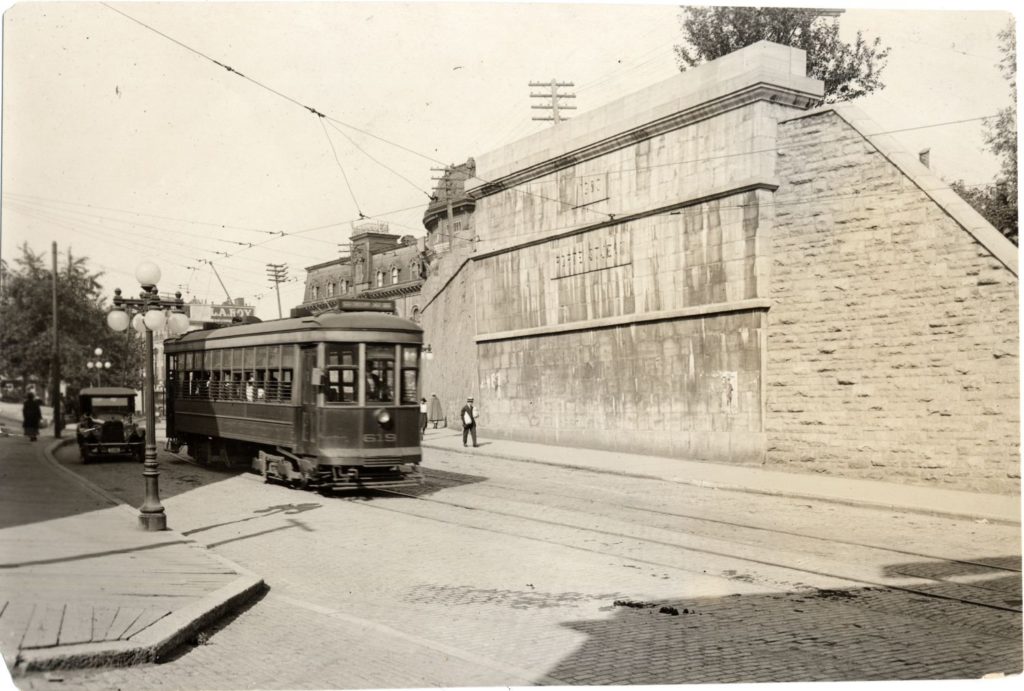

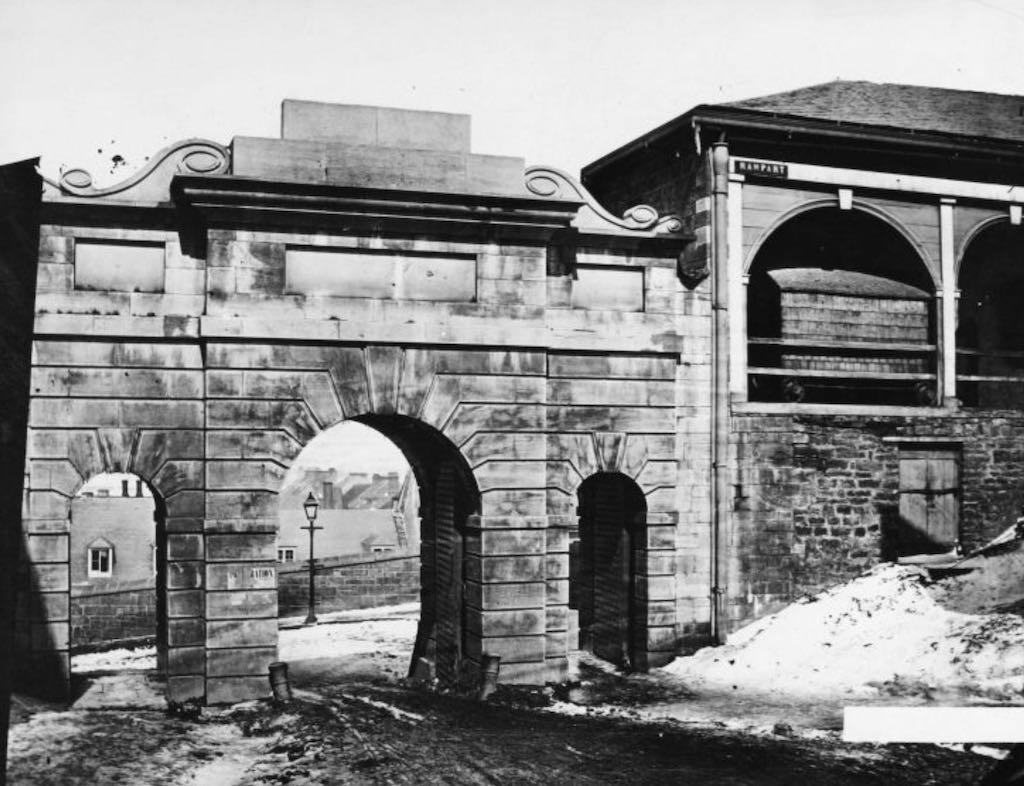

However, there is a major difference: the original French gate was destroyed in 1863, years before the departure of the British army. The reason for this decision by the authorities was quite simple: Saint-Jean street was a major commercial artery and the gate was too narrow for the growing traffic. The compromise reached was to destroy the restricting French gate and build a new one with four narrow paths: two for pedestrians and two for horse-drawn carriages.

With the arrival of the tramway in 1897, this gate has also been destroyed. Today, parts of it can still be seen.

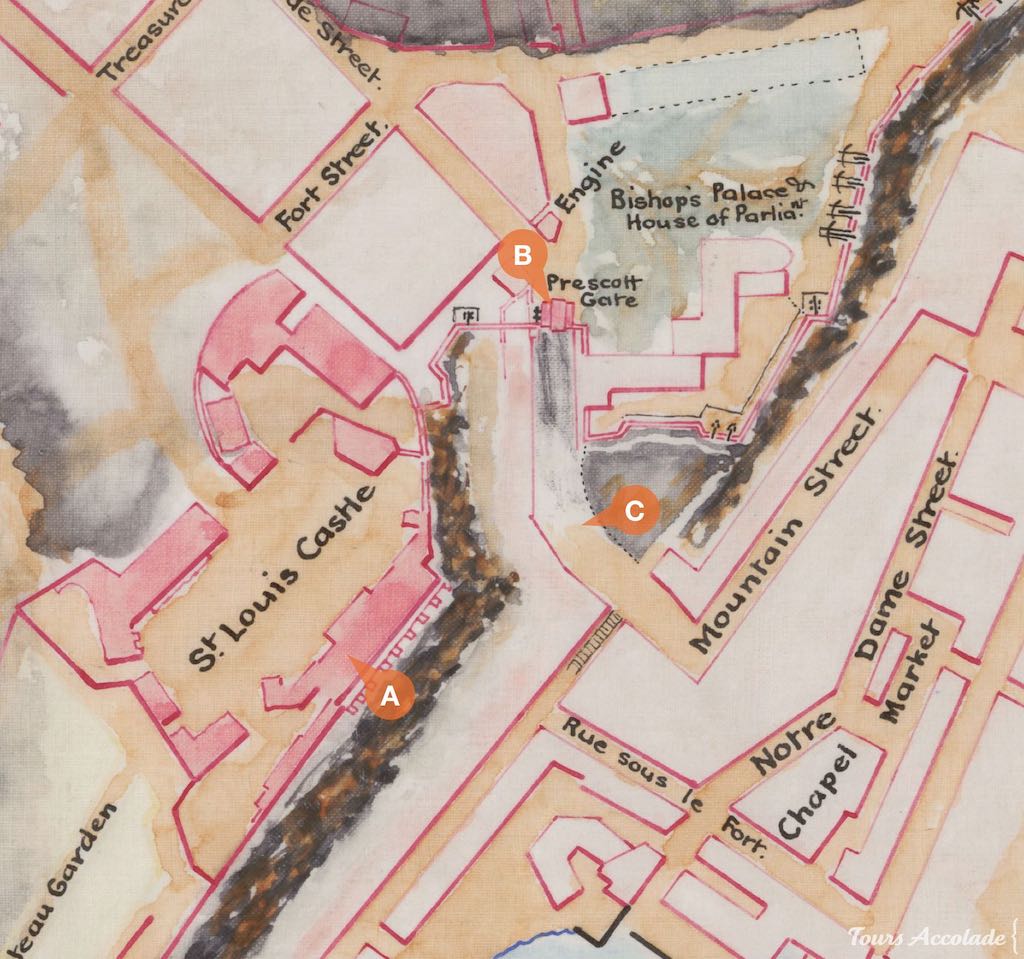

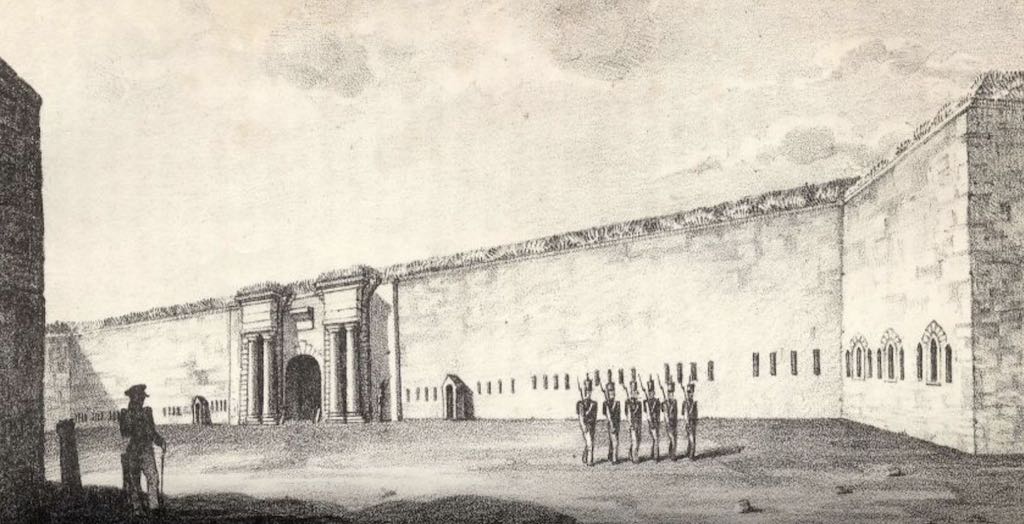

Palais Gates (1740s-1830s-1870s)

The first Palais Gate (also know as Saint-Nicolas Gate) has been built in the 1740s by Chaussegros de Léry. The name refers to the Palais de l’Intendant (palace of the administrator of the colony). James Pattison Cockburn painted it.

As a major entrance gate connecting the Upper Town to the growing Lower Town with its port and St Roch faubourg , the narrow French gate has been replaced by a new and bigger gate in the 1830s.

Nevertheless, this second gate was destroyed in the early 1870s after the British army left, and was not replaced. The new layout of the streets in this area, with a new road on the North-East, made it impossible to build a large gate again and accommodate large vehicles.

Hope Gate (1780s-1870s)

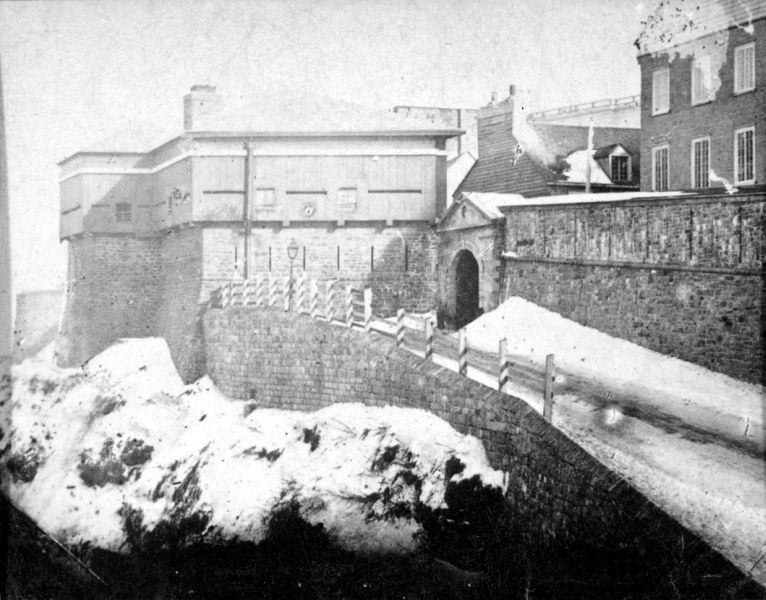

The British improved and expanded the fortifications above the cliff, following the failed attempt by Benedict Arnold to capture the city in 1775-1776. The Hope Gate, named after the Lieutenant Governor of Quebec at the time, Henry Hope, was built as part of these efforts in 1786. The gate was destroyed in 1871.

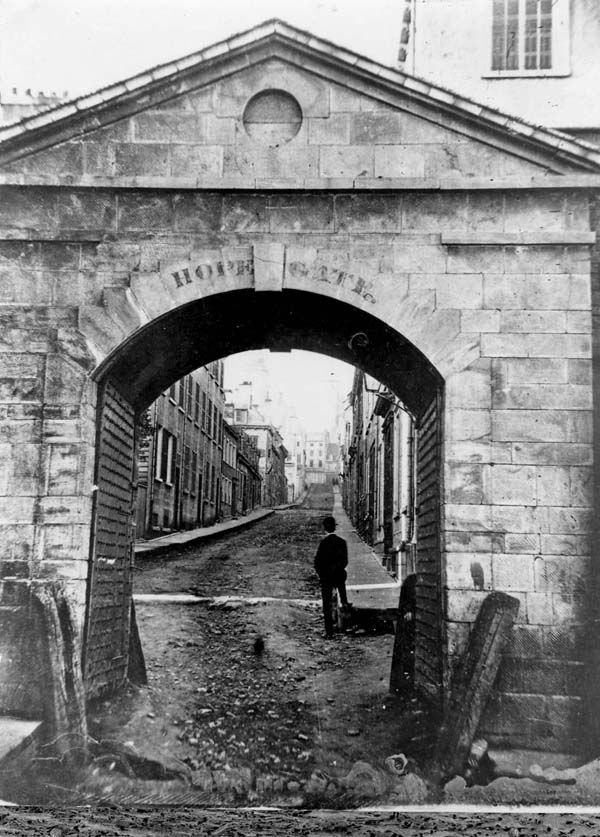

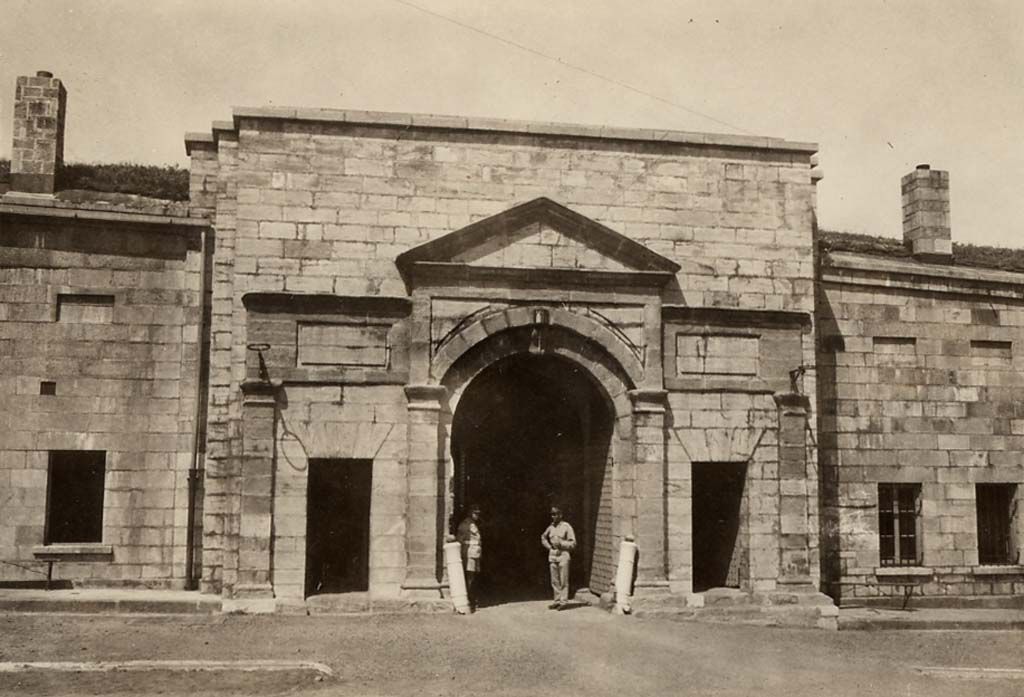

Prescott Gate (1790s-1870s)

Côte de la Montagne is a major natural path that connects the Lower and Upper Towns. During the unsuccessful attempt by Generals Arnold and Montgomery to capture the city, the plan was actually to meet at this strategic location and take the Château Saint-Louis located above. Recognizing the importance of this steep street, the British decided to build a gate there.

In 1797, the Prescott Gate was built, named after the General Governor at the time, Robert Prescott. However, the gate was destroyed in 1871.

Timeless Treasures: The Enduring Gates of Old Quebec

The gates that can be seen today in Quebec City are relatively recent, from the 1820s to the 1980s. Some of these gates feature an ornate, fancy, visually striking design that is reminiscent of medieval architecture, but does not align with the historical reality of the fortifications and gates that existed before. These gates are more intended to convey a sense of nostalgia and romanticism rather than historical accuracy.

Saint-Louis Gate (1870s)

Lord Dufferin successfully persuaded the city to preserve its fortifications and led a project to build a new Saint-Louis Gate, which was designed to accommodate the growing traffic needs. This new gate, built in 1878 was not intended for defensive purposes, as the threat of attack no longer existed. The architectural style of the gate was heavily influenced by the romantic trend of the time, and features a medieval design that is not historically relevant for the time period in which Quebec City was founded, as there were no Europeans present in the area at that time. Nevertheless, this style and the Saint-Louis Gate itself have become integral parts of the city’s identity, contributing to Quebec City’s reputation as a beautiful, heritage-rich city with a romantic and old-fashioned charm.

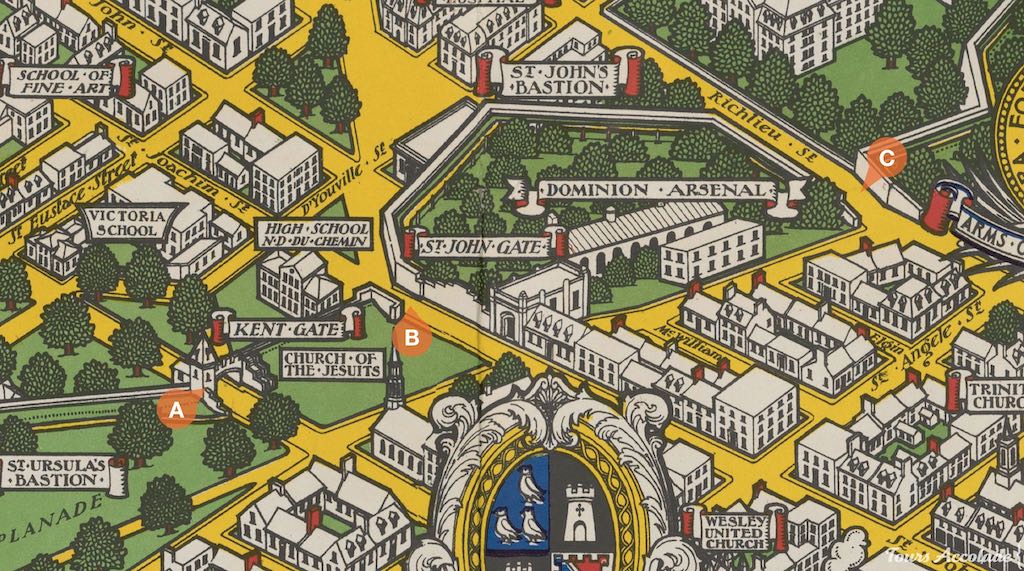

Kent Gate (1870s)

Around the same time as the construction of the Saint-Louis Gate, the Kent Gate was also built with a similar style. It was named after the Duke of Kent, the father of Queen Victoria. This famous ruler of the British Empire sponsored its construction. Notably, this is the only romantic gate in the city that was built in an area where no gate previously existed, but a postern only. The wall in this location had previously been destroyed to open Dauphine street and provide access to the outside of the walled city.

Saint-Jean Gate (1930s)

The previous Saint-Jean Gate was destroyed in 1897 to make way for the tramway, nearly two decades after the construction of the wider and fancy Saint-Louis and Kent Gates. By this time, Lord Dufferin, who had been instrumental in promoting the preservation and embellishment of the fortifications, was no longer in office.

However, during the 1930s and the Great Depression, priorities shifted and many public projects were undertaken across North America to provide employment opportunities for the unemployed. The construction of the Saint-Jean Gate was among these projects and it was built in 1939. The style of the gate is reminiscent of the Saint-Louis and Kent Gates, but with distinct differences in the details.

Prescott Gate (1980s)

A beautiful, old-fashioned gate could have replaced the former Prescott Gate, but unfortunately, funds were limited. It wasn’t until 1983 that a footbridge was built roughly in its place, designed by Paul Gauthier, Gilles Guité, and Jean-Marie Roy and ordered by Parks Canada. The bridge is made of concrete and covered with stones. Just uphill from the footbridge, as a marker indicating the exact location of the previous gate, there’s a date carved into the wall: “1815”, without any explanation. It’s in memory of the year Robert Prescott died.

Dalhousie Gate (1820s)

Finally, among all these gates, which are no longer useful to defend anything, there is one exception: the Dalhousie Gate. This is the gate that gives access to the citadel, a fortress that is still in operation, built by the British in the 1820s under the command of George Ramsay, 9th Earl of Dalhousie, General Governor of Canada.

The citadel is now obsolete but the gate itself has never faced pressure from merchants or traffic. Unlike the other defensive gates mentioned earlier, it was unnecessary to destroy.

Beyond Defense: The Role of Gates in Defining Quebec City’s Identity

As the only fortified city in North America, Quebec City’s gates have become an integral part of its identity. They are prominently featured in the logos of local businesses, used by the tourism office to attract visitors, and even incorporated into the imagery of local sports teams, like the Remparts. The gates serve as a symbol of the city’s rich history and cultural heritage and are deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness of the community. They are not only a physical representation of the city’s past but also a cultural touchstone that contributes to the unique identity of Quebec City.

Experience the Legacy of Old Quebec’s Fortifications

The only original defensive gate still standing today can be found at the citadel, where guided tours are provided. The Saint-Louis, Kent, and Saint-Jean Gates are also worth admiring for their beautiful and picturesque old-fashioned style. They are a reminder of the bold vision of those who built them in the past. We owe much to their legacy today.

We see some of the gates during our public tours, such as Old Quebec: From Pioneers to Citizens and Old Quebec: Winter Walking Tour. Their full history is part of our public tour dedicated to military history and heritage. Additionally, these gates can be included during a personalized private tour of Old Quebec.

Experience history firsthand and discover the rich heritage of Quebec City’s gates on a guided tour. Immerse yourself in the past and uncover the stories behind these iconic structures.

Thank you to Simon Careau and Neil Schomaker for their help.